Today’s Managing Health Care Costs Indicator is $55.2 billion

|

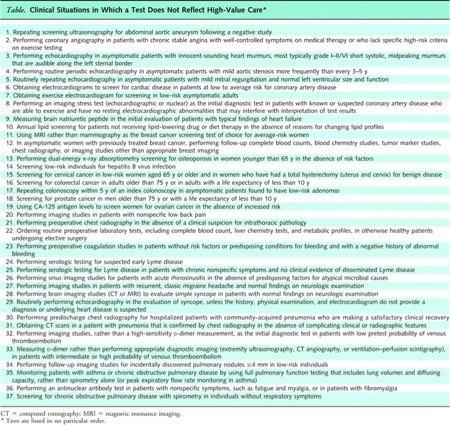

| Click image to enlarge. Source |

Ezekiel Emanuel and Jeffrey Liebman have a post in the New York Times this evening asserting that:

By 2020, the American health insurance industry will be extinct. Insurance companies will be replaced by accountable care organizations — groups of doctors, hospitals and other health care providers who come together to provide the full range of medical care for patients.

I don’t believe it for a minute.

About the indicator above – it’s the market capitalization of United Health Group. Here are the market capitalizations of the other major for-profit health plans:

| Wellpoint | $22.4 billion |

| Humana | $24.6 billion |

| | $15.8 billion |

| Cigna | $12.1 billion |

| | $4.3 billion |

From this link you can see the rise in United Health Group’s stock price over the last year. There were similar increases at Humana and Aetna . $134 billion in market capitalization doesn’t get erased in a mere 8 years – and that kind of market capitalization doesn’t ever go away without a fight.

There are many functions that health plans currently perform that would be better carried out by health care providers. This is true of almost all medical management programs. However, health plans perform some critical functions that won’t go away overnight. Here's why I don't agree with Emanuel's conclusions.

1) Fee for service is not going away anytime soon, and health plans have the transactional engines that make fee for service possible.

a. Many procedures will not fit well into capitation – and these will need to continue to be paid fee for service.

b. Many providers, both physicians and hospitals, are in rural areas where there is little competition. It’s likely that ACO development in those communities will lag – and the population might be too small to pay anything other than fee for service

c. Many patients are likely to travel among different accountable care organizations for their care. Someone will have to transact claims to assure payment of all parties

2) The authors suggest that once ACOs are prevalent, we won’t any longer have to pay all those pesky claims. Au contraire. Successful capitated groups need to track resource use as carefully as fee for service health care providers – so we’ll be completing claims for a long time to come.

3) Health plans are aggressively diversifying. Emanuel mentions that Wellpoint purchased a large Medicare outpatient practice, CareMore, in California Aetna is investing millions in its efforts to be the “back office” for providers establishing accountable care organizations. Cigna has also invested in a number of delivery systems, and most of the major national health plans have purchased boutique health plans that take risk on Medicare Advantage plans.

4) There’s a long history of provider-owned health plans – and it’s not pretty. Provider-owned health plans have generally failed in the past because they’ve had a hard time keeping their costs down. Hopefully, ACOs will be different. However, it’s too early to see how ACOs will perform in the real world.

5) Emanuel and Liebman note that insurance plans are barely offering insurance even now – since most of their members are in self-insured employer sponsored health plans. The insurance companies have figured out how to make these “administrative services only” accounts profitable – and some have actually migrated away from offering fully-insured plans in many markets

6) The authors suggest that with 15,000 members an accountable care organization will be big enough to accept financial responsibility for its entire population. In a non-Medicare population, that number is not actuarially stable, so the ACOs will need to buy some (perhaps expensive) reinsurance to be sure they will not go bankrupt providing care.

The state health exchanges could be a huge boost for local and regional health plans, which in the past have been locked out of a substantial portion of the market. These plans are more likely to be nonprofit, and the Affordable Care Act offers some advantages to nonprofits as well.

The health insurance industry will continue to evolve. The Accountable Care Organization movement could mean a tectonic shift for insurers – but I don’t see them disappearing any time soon.